Electrical dental drills heat up as they start to wear with time. This has lead to many reports of facial burns. The drill may not feel hot to the dentist – the burn being a product of time, pressure and temperature.

Electrical dental drills heat up as they start to wear with time. This has lead to many reports of facial burns. The drill may not feel hot to the dentist – the burn being a product of time, pressure and temperature.

Healthcare can persist with it’s usual response to this: find a dentist or nurse at fault, line lawyers pockets and persist in leaving patients with permanent facial disfigurement.

Alternatively we could do something effective to stop this problem:

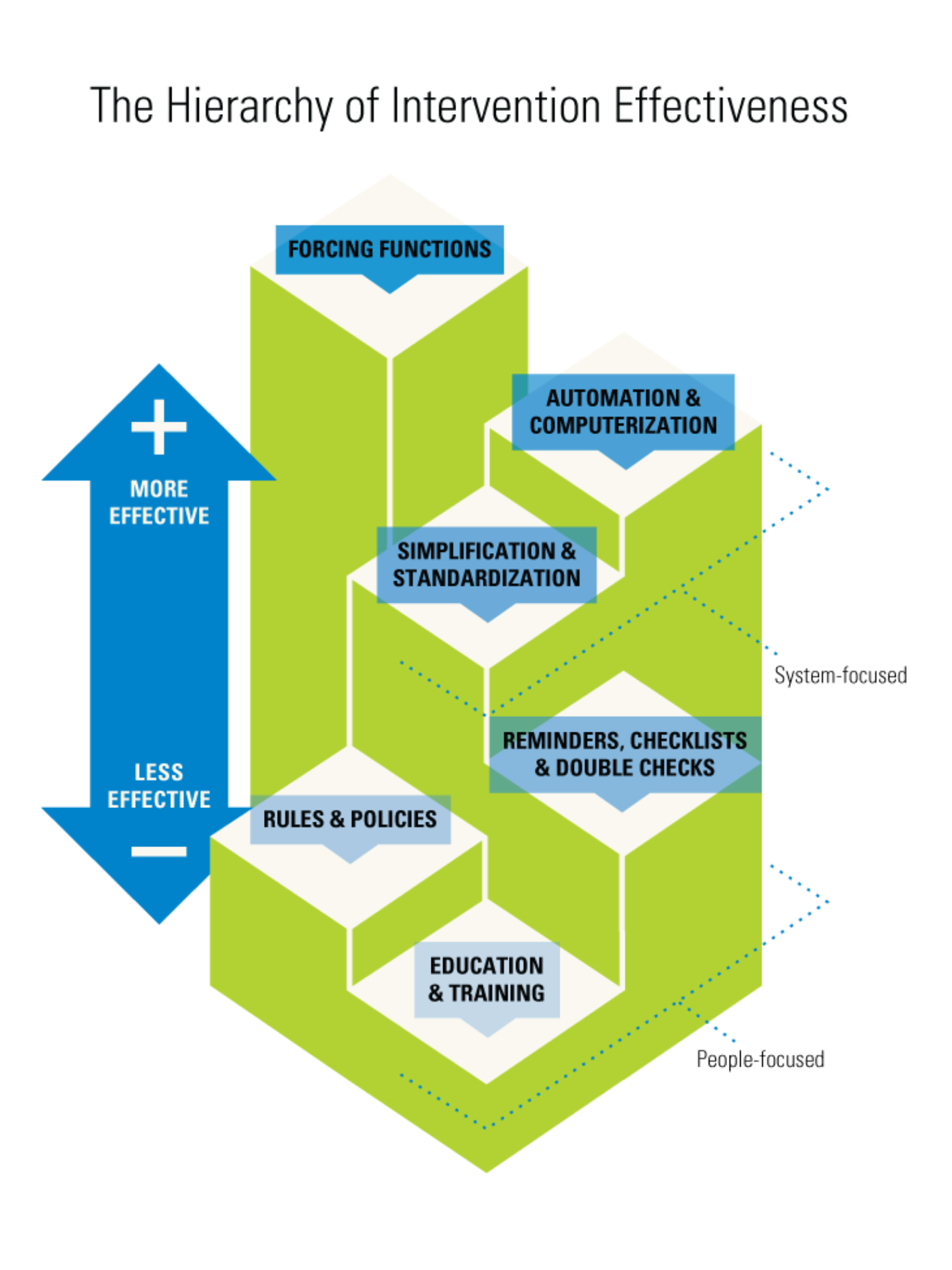

Dental drills which automatically cut out and stop working if they begin to heat up already exist (see here). Their use should be made compulsory – this is a ‘forcing function’, effectively designing the problem out.

Help:

Please sign the petition to make standard dental drills which don’t heat up (click here).

Please let us know of any similar cases not already presented on this post.

Please click on each image to read the story behind it:

These are just some of the stories from the internet (click on each):

Recently a friend showed me a lesion on her face she’d noticed after having dental work. Immediately I thought of facial burns from dental drills.

I was first made aware of this issue by a colleague who was acting as an expert witness in a case. Focus had been put on the dentists poor technique and the dental nurses failure to ensure the drills had been appropriately maintained.

This is the name,blame,train, and shame safety culture that we currently exist in – and whilst demoralising for front line staff it also does not stop the problem from recurring.

The FDA sent out an alert in 2007 regarding this issue. After numerous further cases they sent out another alert in 2010. Perhaps this illustrates the ineffectiveness of safety alerts.

It struck me at the time that no one was addressing the real hazard – the drill.

The human factors approach is: ‘We don’t redesign humans. We redesign the systems within which humans work.’ – basically it making it easier for front line staff to do their jobs right.

Electrical drills, as they start to fail, will actually speed up and generate heat. They only need to heat up to 48C to cause burns (unlikely noticeable by the gloved hand) – the burns being a product of heat and time. Unfortunately often the first sign a drill is failing is a facial burn – obviously not great feedback.

At last a refreshing article that, without naming it, clearly utilises the human factors approach to patient safety, and promotes a drill that will not heat up:

Handpieces and the Risk of Patient Burns – Reducing the risk of thermal damage with new technology.

You will note a hint of frustration: ‘The FDA may be on high alert regarding patient safety, but industry-wide safety regulations are yet to be formulated’.

If the FDA do introduce these regulations then we all win. Front line staff are provided with the safest environment, patients avoid the risk of facial burns, hospital indemnity premiums don’t go up, and insurers don’t pay out for another inevitable adverse event.

Front line staff are best placed to recognise the hazards that exist in their workplace. Their ability to do this could be improved through greater education about the human factors approach to patient safety. The ‘Hazard Feedback Framework‘ (or something similar) could be used to help develop solutions at the coal face. Human factors experts could guide this process. The FDA / TGA / indemnifying insurers could be provided with information about the hazards. We would all benefit from having the hazards removed from our workplace.

In the meantime I will make sure my friend informs her dentist he may have a problem with his drill before another facial burn occurs and the insurers pay out.

For a great introduction to human factors in healthcare please watch this presentation by Dr Terry Fairbanks.

5 Comments