The Hospital Emergency Number (also known as cardiac arrest or crash call number) is an internal hospital phone number which when dialled is rapidly answered by switch board (the usual phone number for switchboard at times may take minutes to connect during times of high phone traffic).

It is used in the event of an emergency (eg a cardiac arrest when no arrest buzzer exists nearby).

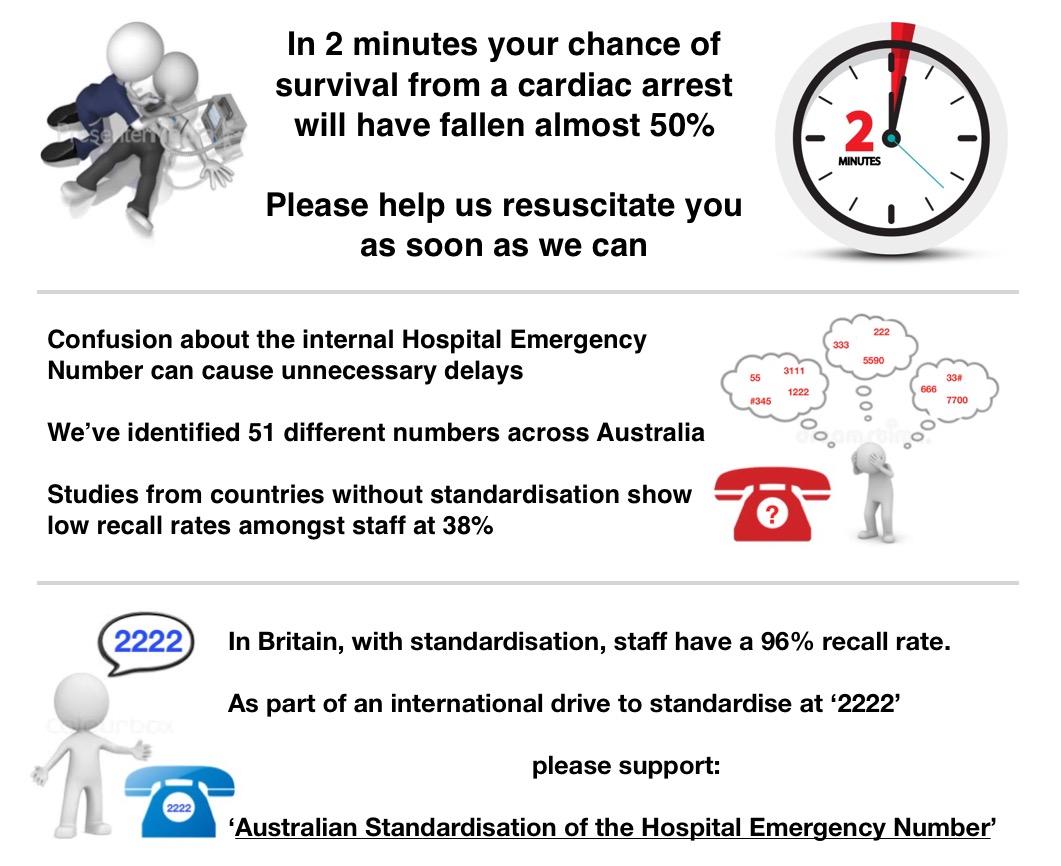

The most important determinants of survival from cardiac arrest are early defibrillation and early effective cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), with survival decreasing by 10% per minute (1). Time to the arrival of a cardiac arrest team has been found to be inversely related to the survivability of an in-hospital cardiac arrest and likelihood of discharge from hospital (2).

The first step in the AHA “chain of survival” remains early access- early recognition, access to and activation of the medical system (3). For an in-hospital cardiac arrest, this first step is achieved either by activating an alarm in critical care areas (see ANZCA PS 4, PS 55) (4) or dialling a hospital emergency number (HEN).

However, activation of the HEN is not straightforward: in an ongoing survey of Australian hospitals and health care facilities, over 48 separate HENs have been identified over 267 institutions (approximately 29% of all identified hospitals and health facilities) (5). Different numbers are found within a single local health districts or area health services. In some cases, different HENs are found in co-located institutions or the HEN changes depending on the time of day.

Errors in communication regarding the HEN was found to occur in 13% of studied deaths from in-hospital cardiac arrests (6).

A post- implementation survey in the UK showed a 96% correct recall rate of the nationally-standardised 2222 HEN (7). This contrasts to a Danish survey which showed a 38% correct recall where the HEN was not yet standardised (8).

“Standardisation has been shown to be an effective mechanism for reducing human error in complex processes or situations. Conversely, the lack of it can increase risk and make human error more likely and in some cases inevitable” (9).

“In health care, evidence shows that divergent patterns of care result in worse clinical outcomes and that removal of variance can reduce risk, inefficiencies and costs… The standardization of hospital processes should enable trained health care workers to perform effectively in any facility in the world” (10).

These are some of the comments we received from our ongoing survey from hospital staff in Australia regarding the Hospital Emergency Number:

I have a feeling it’s something ridiculous like 7555 but I can check today

There is a tiny private hospital there. I work both places and it drives me nuts that the numbers differ.

Might be useful to also get data on doctor movement. I currently work across 4 sites (3 public, 1 private) and have worked in 16 hospitals in 19 years.

The variation between hospitals drives me crazy so thank you for advocating for standardization!!!!!

Thinking if I just smash my hand on the keypad repeatedly some help will come eventually I asked today. It’s 222. I thought it might be 777.

Some hospitals are 55 I think. I agree it should be standardised especially given the large body of transient staff in hospitals eg registrars.

Um…88 I think

I do work in a hospital where it actually changes depending on the time of day. Good to keep us on our toes & guessing what it might be.

Me: dials 99 Switch: hello? Me: hello, code blue (location) please Switch: (sounds stricken) sorry I’d have picked up earlier but this isn’t the emergency number, that’s 4444 Me: sorry, I didn’t know, can you call the blue for me? Switch: yes, yes, absolutely

References:

1. Larsen MP, Eisenberg MS, Cummins RO, Hallstrom AP. Predicting survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a graphic model. Ann EmergMed. 1993;22:1652–1658.

2. Sandroni, C., Ferro, G., Santangelo, S., Tortora, F., Mistura, L., Cavallaro, F., Caricato, A., and Antonelli, M. In-hospital cardiac arrest: survival depends mainly on the effectiveness of the emergency response. Resuscitation. 2004; 62: 291–297).

3. Cummins RO, Ornato JP, Thies WH, Pepe PE (1991). “Improving survival from sudden cardiac arrest: the “chain of survival” concept. A statement for health professionals from the Advanced Cardiac Life Support Subcommittee and the Emergency Cardiac Care Committee, American Heart Association”. Circulation. 83 (5): 1832–47.

4. http://www.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents accessed

5. https://www.psnetwork.org/australian-standardisation-of-the-hospital-emergency-number/

6. Sukhmeet S. Agnieszka M. Ignatowicz, Liam J. Donaldson. Errors in the management of cardiac arrests: An observational study of patient safety incidents in England. Resuscitation, Volume 85, Issue 12, December 2014, Pages 1759-1763

7. Whitaker DK, Nolan JP, Castrén M, Abela C, Goldik Z. Implementing a standard internal telephone number 2222 for cardiac arrest calls in all hospitals in Europe Resuscitation 115 (2017) A14-A15.

8. A call for 2222 in European hospitals—A reply to letter by Dr. Whitaker Lauridsen KG, Løfren B Resuscitation, 2016-10-01, Volume 107, Pages e19-e19.

9. https://chfg.org/uncategorized/chfg-standardisation-survey-results/

10. Agnès Leotsakos, Hao Zheng, Rick Croteau, Jerod M. Loeb, Heather Sherman, Carolyn Hoffman, Louise Morganstein, Dennis O’Leary, Charles Bruneau, Peter Lee, Margaret Duguid, Christian Thomeczek, Erica van der Schrieck-De Loos, Bill Munier; Standardization in patient safety: the WHO High 5s project, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 26, Issue 2, 1 April 2014, Pages 109–116